IN-DEPTH: The history of the Glashütte watch region

Fergus NashGerman watchmaking today is given the same reverence as the Swiss, if not even more in some cases. But many people aren’t aware that the beating heart of their industry is entirely located within one small town of only 7,000 people. Glashütte in Saxony, Germany has been the epicentre for German watchmaking prestige for nearly two centuries, but despite the glamour of their 10 current watch companies, the region has had a tumultuous history. From lacklustre resources to natural disasters and controversial lawsuits, every setback has just made the Glashütte community and industry stronger than before.

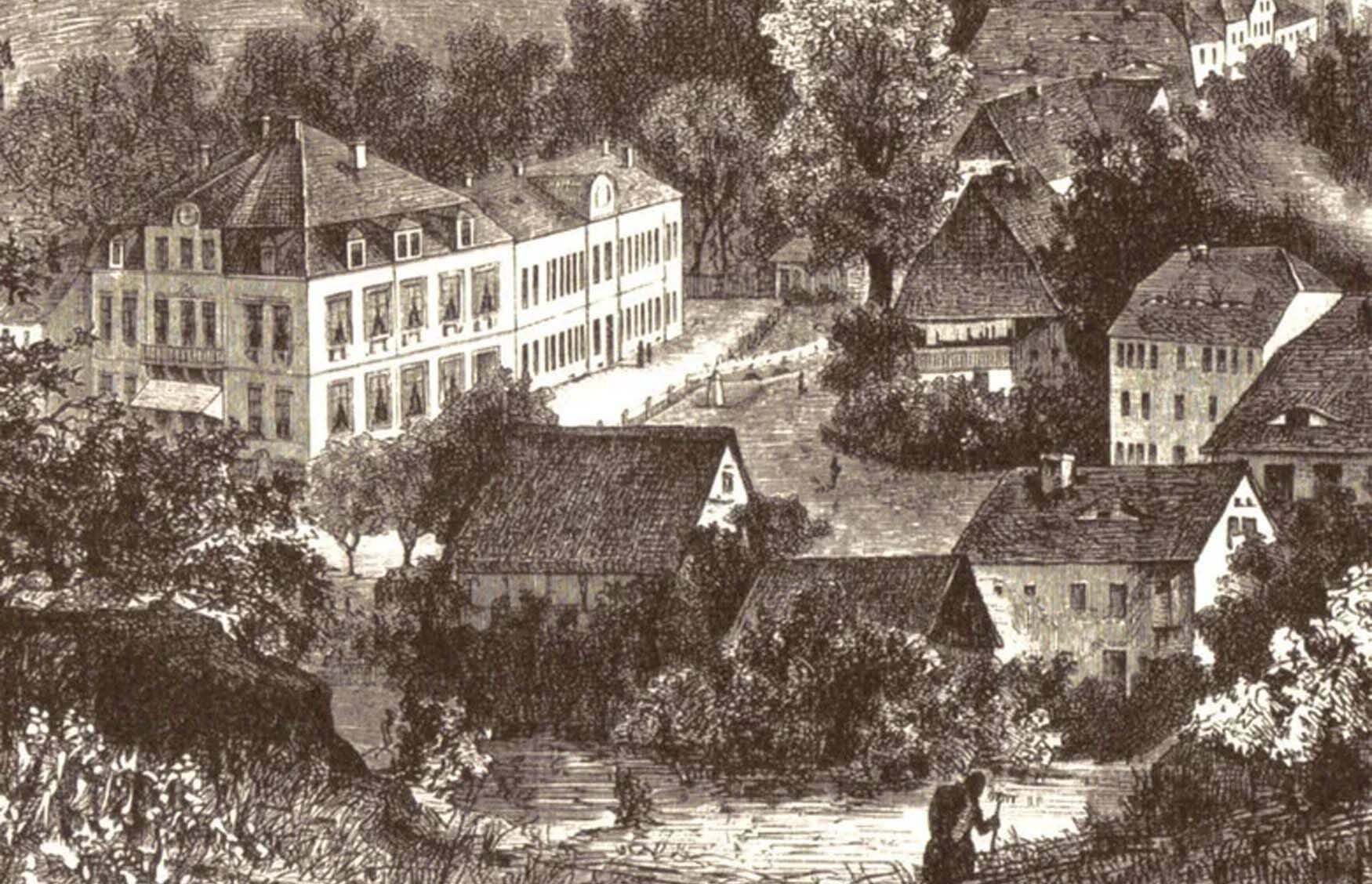

While many watchmaking communities around Switzerland rose up out of pre-existing towns taking advantage of emerging technologies and business practices, it seems that Glashütte was more or less willed into existence. It’s likely that forest glass was made there, earning the literal translation of “glass hut” as its name, until it was destroyed by the Hussites in 1429. It wasn’t until 1490 that the discovery of silver ore had the town officially chartered, but within a couple of decades it had become apparent that deposits in surrounding areas were more deserving of mining efforts. A few attempts at reviving the mines encouraged more buildings like churches to be constructed, but as 250 years had passed with only 10 tonnes of silver and 150 tonnes of copper recovered, the mines were abandoned as a commercial failure. Faced with a near-worthless town, the Royal Saxon Ministry of the Interior had to come up with an alternative value.

Ferdinand Adolph Lange was born in Dresden, the capital of Saxony, and was given an education thanks to foster parents. At 15 he studied at Dresden’s Royal Technical Educational Institute and apprenticed under the Saxon court watchmaker Johann Christian Freidrich Gutkäs Senior, quickly making a name for himself. Fifteen years later in 1845, the Royal Saxon government granted Lange a 7,800 Thaler loan to set up a watch company in Glashütte, attempting to save the town’s flailing economy and provide some employment. Turning down a lucrative offer from the Austrian watchmaker Joseph Thaddäus Winnerl to work for him in Paris, Ferdinand Adolph Lange decided to forge his own company A. Lange, Dresden in the dying mining town. It’s ironic to consider how much of a luxury brand A. Lange & Söhne has become, since the original vision for the company was one of economy and cheap labour. Fifteen straw-weavers were to become watchmaking apprentices, and some of them would go on to bolster the Glashütte watch industry further by founding their own companies.

Although A. Lange, Dresden began with a penny pinching attitude, Ferdinand’s inherent skill wouldn’t be wasted. He made sure that there was enough focus given to individual components, and even invented new precision tools that helped his pocket watches become not only affordable, but accurate. The company became A. Lange & Söhne when his son Richard joined in 1868, and by 1870 they had 70 employees. The sons took over the majority of the company’s management in those years, as Ferdinand had spent 1848-1866 as Glashütte’s mayor and wished to pursue politics. Sadly, he died suddenly in 1875 before the company he built had reached worldwide fame. Richard Lange had also been a trained watchmaker, and introduced such rare complications as dead-beat seconds and power reserve indicators, but also had to step down from the company for health reasons. Friedrich Emil Lange, the other of Ferdinand’s sons to join the brand, wound up taking control.

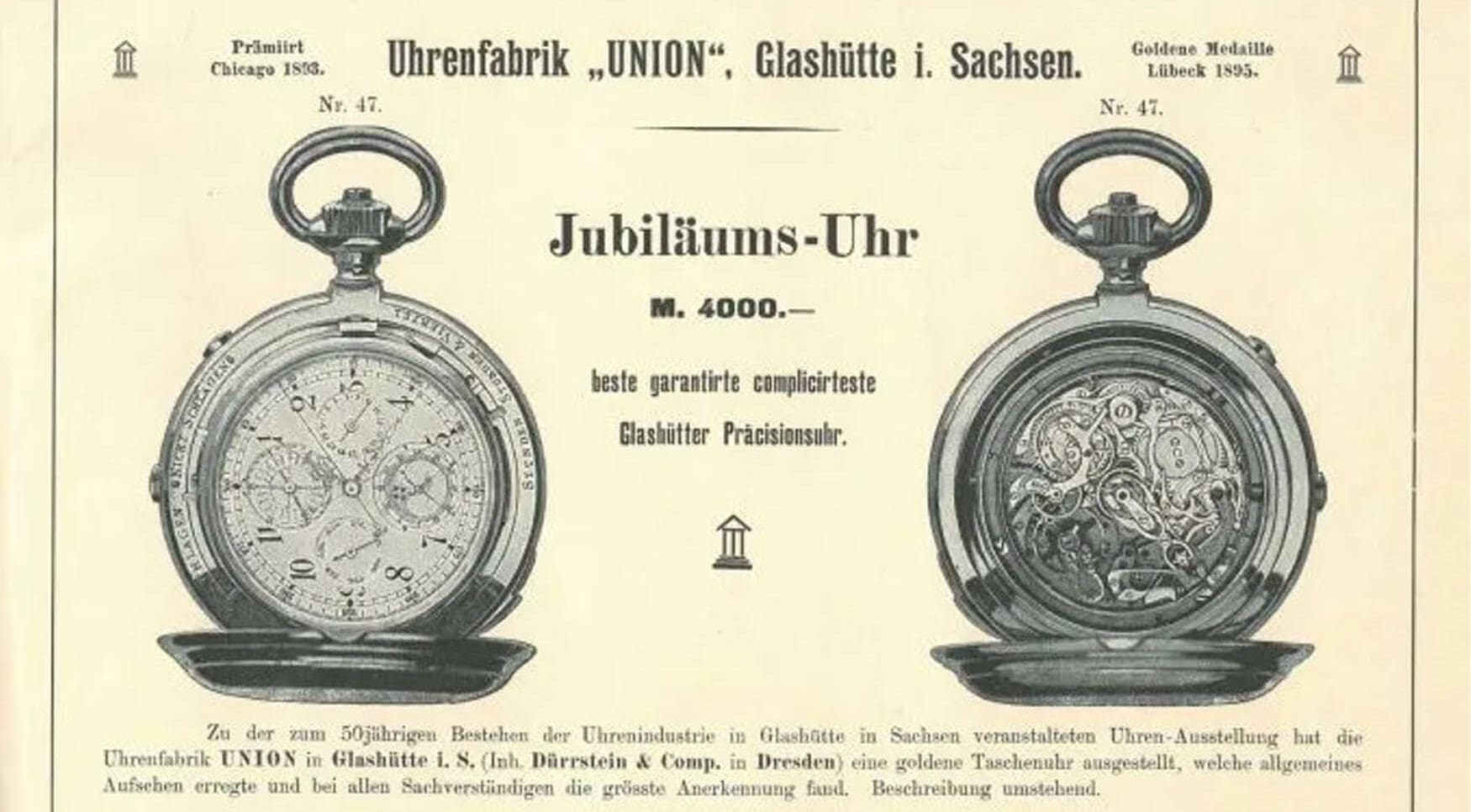

Towards the end of the 19th century, A. Lange & Söhne began producing naval chronometers which led to a boom of business, requiring the factory to be expanded in 1898. Between these and their ostentatious Grande Complication watches in solid gold cases, their reputation had skyrocketed across both Europe and the United States. Of course, they weren’t the only watchmakers in Glashütte anymore. The J. Assmann factory was founded by one of Ferdinand Lange’s apprentices back in 1852, and had seen great success through the Glashütte precision pocket watch, as well as producing more affordable options as A. Lange & Söhne prices continued to rise. It was also partially responsible for the rise of Gruen watches in the USA, as the founder’s son Paul Assmann collaborated with Fritz Gruen who had attended the German Watchmaking School in Glashütte. Union Glashütte also opened in 1893, with the founder Johannes Dürrstein moving back from Switzerland to produce more affordable German watches.

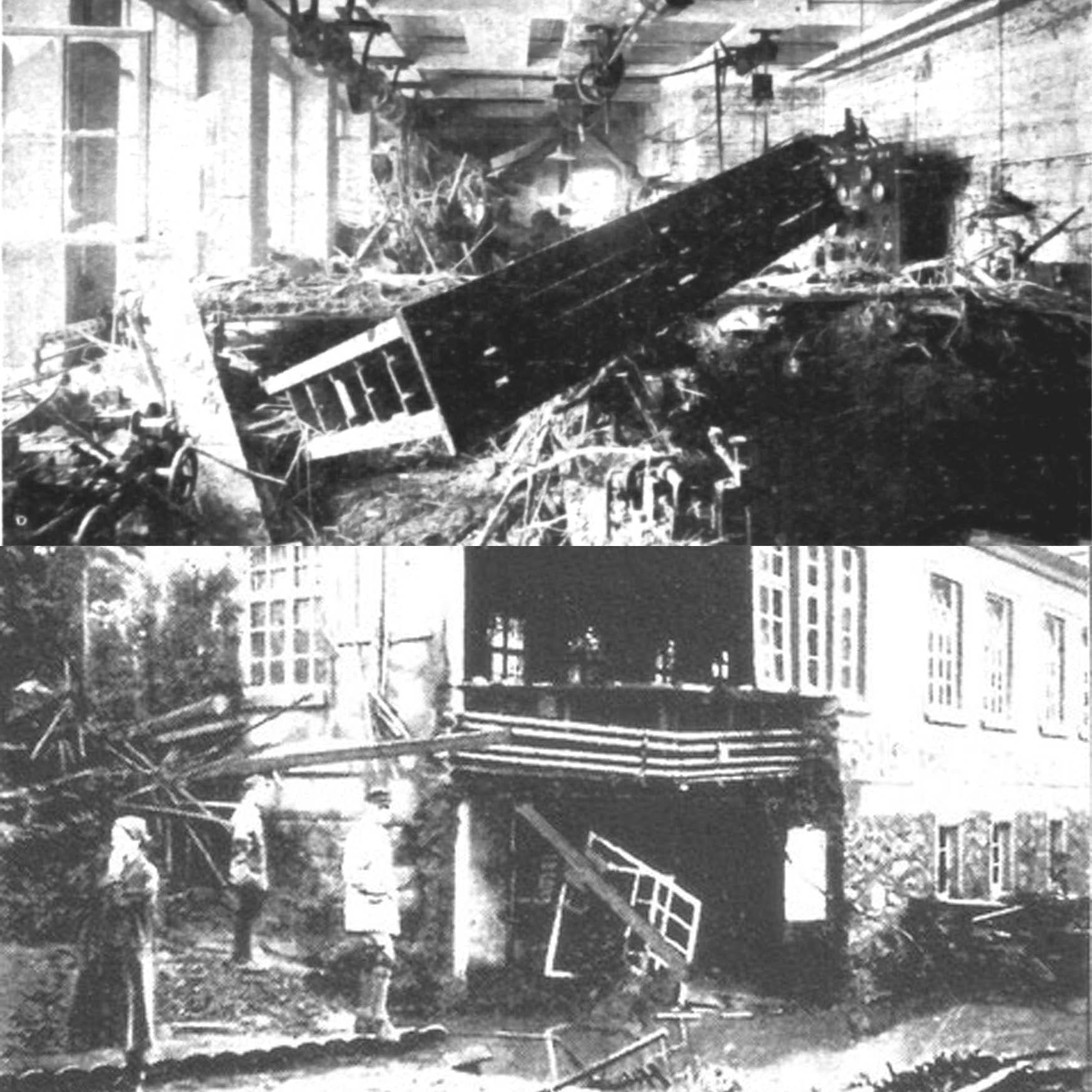

The early 20th century held great promise for the rising star of Glashütte, with A. Lange & Söhne at the helm of their finest exports. Unfortunately for Germany, the beginning of the First World War did not present the same economic boom that it did for Switzerland. The government needed gold wherever they could find it to pay for the war, and solid gold pocket watches were among many items that were sacrificed. Even if someone wanted to buy a cheaper watch, hyperinflation well and truly destroyed consumer business and many companies were forced to produce watches for the German armed forces in the meantime. Big companies such as A. Lange & Söhne even had to print their own emergency money for local use, and things only got worse after the war ended. By 1926, unemployment in Glashütte was at an unfathomable 85%, and a devastating flood took at least 150 lives and tore through many of the factories. With water levels of above four metres the buildings were filled, meaning that all of the machinery had to be dismantled, treated, and reassembled to prevent whole factories from rusting. A whole corner of the Paul Stübner watch factory was torn away, many valuables disappearing along with it.

Despite global events and the planet itself beating Glashütte down, innovation and perseverance didn’t stop. A. Lange & Söhne created a spin-off brand in 1925 at lower prices, proving their desperation. Richard Lange created the Nivarox alloy for hairsprings in 1931, but sadly the 1930s witnessed the closure of many other companies such as Union Glashütte in 1933. As the Nazi regime took hold of Germany and World War Two began, the struggling Glashütte would endure its darkest time. Once again back to producing exclusively military watches, the factories of Glashütte were filled with approximately 3,000 prisoners of war in forced labour by 1943 — almost equalling the population. On the final day of the war in 1945, Glashütte was bombed. The A. Lange & Söhne factory was completely destroyed and many other factories damaged, then the town was occupied by Soviet forces. Whatever could be salvaged was nationalised or sold off as reparations.

By 1951, all of Glashütte’s watch production had been combined into a single company called VEB Glashütter Uhrenbetriebe, and there are a few rare examples of watches produced during these tumultuous years with confusing dial labels. Glashütte watches, although now mass-produced, were still well-regarded though. The Spezimatic and Spezichron watches from the ‘60s and ‘70s are still some of the coolest designs from the era, and they also founded the basis for what would become Glashütte Original. As time went on, the dream of German reunification edged closer to reality, and the process began in 1989. Released from state control in 1990, Glashütter Uhrenbetrieb GmbH became a legal entity holding much of the historic copyrights and trademarks, opening the door for other brands to return too. The 1990s and early 2000s witnessed a boom of resurrections such as A. Lange & Söhne, Union Glashütte, Mühle Glashütte, and Nomos Glashütte.

Some brands focused on their heritage like the naval chronometers of Mühle Glashütte, while others had to figure out their new identities in a world without pocket watches. The Swatch Group acquired both Glashütte Original and Union Glashütte, retaining full German production with the financial and logistical aid of a Swiss mega-corporation.

Nomos in particular have quite an interesting historical parallel, as they were both the subject and instigator of separate lawsuits almost 100 years apart. When the brand was founded in 1906, their business model was largely importing Swiss watches and selling them under the Glashütte name. They were sued in 1910 by A. Lange & Söhne and were forced to close. Having returned in name alone in the ‘90s, the modern brand has pretty much nothing to do with the 20th century one. When Mühle Glashütte were using too many Swiss components in the early ‘00s, Nomos were the ones to sue them and bring them to bankruptcy. Thankfully, a solid insolvency plan saved Mühle and led to firm legal precedent for the protection of the Glashütte identity. That unwritten rule was made official in 2022 as the regulation for the protection of the indication of geographical origin Glashütte.

Today Glashütte is completely synonymous not just with German watchmaking, but German excellence. From centuries of disappointing mining efforts to floods and bombings, it’s almost as if the town has got a resilient will of its own.