IN-DEPTH: How a fatal train crash became the catalyst for the Ball Watch Company’s success

Fergus NashThe domination of the Swiss watch industry feels like an eternal truth, especially given the age of some of the most popular brands which stretch back hundreds of years. They may have always had the upper hand when it came to high-end complications and ornate decoration worthy of royalty, but there was a period of time when if you wanted accuracy, then you wanted American. The reasoning behind this lies with the revolutionary United States’ railroad network, and specifically the role played by Webb C. Ball.

The history of railroads anywhere in the world is incredibly complex, and even more so in the United States. Multiple inventors and companies were working overtime to set the new standards, with innovation after innovation all competing for domination in the mid-19th century. Despite the first American train station opening in Baltimore in 1830, it wasn’t until 1883 that the railroads adopted standardised time zones to help coordinate their operations. At that moment, Webb C. Ball was working as a jeweller and using time signals from the United States Naval Observatory, helping keep Cleveland in sync.

Come 1891, the catalyst that changed US timekeeping forever was a tragic inevitability. Aboard a train named the Toledo Express, an engineer’s watch was running four minutes’ slow. They were aware they had to give way to a passing fast mail train, but didn’t know they were running behind schedule. Near Kitpon Station west of Cleveland, the mail train spotted the slow-moving Toledo Express too late, and no amount of braking could prevent the incoming catastrophe. With coaches made primarily of timber, the two trains telescoped on impact, crushing the structures and claiming the lives of six postal clerks and two engineers. Pictures of the horrendous wreckage spread across the nation, creating a desperate call for safety reform.

It’s a sad reality that almost every safety progression in modern history has been preceded by a horrific event, but martyrdom is the most powerful way of prioritising change. The 1891 crash in Kipton was actually the fifth recorded train crash in the United States where a pocket watch was found to be running slow, proving that this was much more than an isolated incident. As Webb C. Ball held an excellent reputation for timekeeping within Cleveland, he was chosen by members of the US Congress and Lake Shore officials to dictate a set of standards for railroad chronometers, similar in concept to the accurate marine chronometers of the time yet able to fit in a railway worker’s pocket. These strict standards formed the inspiration for COSC certification we’re familiar with today, and since their introduction in 1891 there was only one more train crash in 1893 with a faulty watch to blame. After a death toll on the rails that had climbed to 50 lives, the work of Webb. C. Ball helped to prevent more accidents.

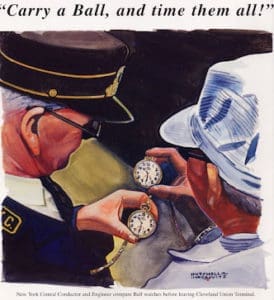

Although The Webb C. Ball Watch Company started off by tinkering with and recasing movements from such American icons as Hamilton, Elgin and Waltham, the mark of the Offical Ball Standard on the dial started to find a place in the hearts of consumers. As the turn of the century arrived, Ball was marketing itself on the merits of its accuracy, reliability, and possibly even coining the phrase to be “on the Ball”. The 1920s saw the popularisation of the wristwatch for men, and Ball successfully rode that trend with a variety of Art Deco inspired cases. While their pride for railway chronometers never left, Ball followed the field stylings of the 1940s, the sporty sophistication of the 1950s, and even pioneered the idea of a retro reissue with the Trainmaster in the late 1970s.

Moving into the 21st century, Ball are no longer independently owned, but they have undoubtedly kept up with modern watchmaking in both design and technology every step of the way. Adhering to one of their old slogans “accuracy under adverse conditions” and similarly to their original business model, their ranges tend to use Swiss-made movements from third parties such as ETA and Sellita with COSC-certified accuracy. The railway history still runs deep within their catalogue, especially with lines such as the Official Railroad Watch and the Trainmaster, but they also offer sporty daily-wearers and divers in the Engineer ranges.

Of course, watch brand history should always be taken with a grain of salt. We can be grateful that Ball’s story is fairly linear and well-documented, however there are always going to be other points of view. For example, while 1893 was indeed the final time a train crash was caused by a slow-running watch, it was also the same year that the Railroad Safety Appliance Act mandated air brakes and automatic couplers on all trains, vastly reducing the chances of collisions and minimising casualties in their event. Whether you’re convinced of Ball’s singular importance to watchmaking, or more dubious of their marketing, one certainty is that they’re a watch brand well worth checking out.